Monday, 28 April 2025

10:07 AM

I saw a post on the social medias that asked something like "If I'm in a Turn Only lane already, do I need to have my blinker on?" It got me thinking about the whole question of when and why to use the blinkers (on your car, in case that's not clear).

I should start by noting that using the blinkers is a way of telling other people what your intention is. You, obviously, know where you intend to go.[1] The question of whether to use blinkers is therefore really one of whether it's useful for these other people to know your intentions.

The short answer: yes. In the most general case, your blinker tells the driver behind you[2] that you intend to do something besides continue going straight. (It also explains why you're stopped in the middle of a street.) It also tells drivers coming at you that you intend to turn, which might involve crossing their lane.

The I'm-in-the-Turn-Only-lane inquirer was probably thinking about these other people — the driver behind you and potentially drivers ahead of you. In most cases, traffic-flow markers probably make it clear to them what you intend to do, so why do you need a blinker?

Well, there are other people who aren't drivers who would also like to know your intention. One group is bicyclists, who are often squeezed into a lane to your side and whose bike lane might not in fact be a turn-only lane.

Another group is pedestrians, who might not even know that you're in a turn-only lane. The sorts of control signals that drivers have — right- or left-turn arrows on the traffic light, signs hanging above an intersection, and/or arrows on the pavement — are often invisible to someone standing on the curb. (See earlier photo.)

I think this is relevant even on the freeway when there are Exit Only lanes. In theory, you're in an Exit Only lane because you intend to get off at that exit. Once you're in that lane, do you need to keep your blinker on?

Yeah, well. People being people, sometimes drivers realize too late that

they're in an exit lane or turn lane, oops, and they will sometimes make a, mmm, unorthodox move to avoid the exit or turn. Keeping the blinker on while you're in an Exit Only lane or Turn Only lane reassures drivers behind you that you do intend to exit or turn and, importantly, that you're not going to lurch back in front of them.

I also discovered an unexpected benefit of using blinkers when I got my late-model-ish car (2022). The car has proximity warnings that tell you when someone is to your side. The default is a visual on the dashboard and in the relevant side mirror.

But if you have the blinker on, you also get an audio warning. This has been fantastically helpful for driving in the dark in the rain — I can change lanes with confidence even if visibility is not ideal.[3] So I use my blinkers with gusto.

Back to the original question: Do I need to use my blinker if ... ? Yes. Redundancy is just fine in communications, especially in situations where misreading something can result in crashes. As I say, you know where you're going, but the more information that other people have about how cars are moving — not just drivers, but everybody — the better.

Speaking of blinkers, there's a related question about when the appropriate time is to put your blinker on. Apparently people have very different ideas about this, but we can think about that another time.

__________

[categories]

general

|

link

|

Friday, 31 May 2024

12:04 PM

The surest way to cast a critical eye on the amount of stuff that you have is to prepare for moving. The prospect of boxing up all that stuff and hauling it and finding a place to put it at the new domicile can lead a person to wonder why they even need all that. This is particularly true when you're downsizing from, say, a four-bedroom house with a double garage to, say, a two-bedroom condo with a single outdoor parking space.

We did this some years ago, which resulted in a huge yard sale and a sometimes-painful culling of all our stuff, especially books. But we did it, and in our little place we're a wee bit tight, but we manage.[1]

Chapter 2. Over this last winter, we spent about six months in San Francisco for my wife's work. During that time we lived in rentals. When we drove down, we took what we needed in one large suitcase and two small ones.[2] We bore in mind the sensible travel advice that you don't have to bring everything with you — your destination has drugstores and clothing stores (and for me, hardware stores, ha).[3] So while we were in SF, we made trips to Target and Daiso and other locales where we could fill in any missing stuff.

This worked well. Our rentals had laundry facilities, of course, so I was able to cycle through my limited wardrobe. And we were indeed able to get the additional things we needed — my wife needed some work clothes, for example. This worked well. Our rentals had laundry facilities, of course, so I was able to cycle through my limited wardrobe. And we were indeed able to get the additional things we needed — my wife needed some work clothes, for example.

But we bore in mind that these acquisitions were either temporary (to be left behind at the rentals or donated) or we'd have to haul them back with us. This mentality helped frame the question of whether to buy stuff: for everything that we acquired, what were we going to do with it when our stay in SF ended?

(One place where this kind of failed was with books — between visiting a gajillion bookstores and going to weekly library book sales, we acquired more books than we probably should have. I ended up shipping books back home via the mail before we left.)

Chapter 3. Back in Seattle! After unpacking the suitcases, I went to put away the wardrobe that had served me well during our extended leave. But when I opened my dresser drawers, I was kind of shocked: I have so much stuff. I had been living with a collection of, like, 9 or 10 shirts. But at home I have two full drawers full of neatly folded t-shirts. Why? Why would I need a month's worth of t-shirts? I had the same experience in my closet — why do I need all these shirts/pants/sweatshirts/coats?

Well, I don't.

So another culling has begun. These days, when I pull out a shirt, I might look at it, and say yeah, no, you go in the Goodwill pile. This process is not as concentrated as if we were moving again, but it's steady and I'm determined to keep at it until I'm down to a collection of clothing that I actually use. Ditto kitchen stuff, linens, office supplies, leftover project hardware, and all the other stuff that just accumulates. (Books, mmm, that one's hard.)

Taking a break from our stuff, and living adequately with less of it, has really helped us look at it again with a bit of a critical eye. I suppose "Do I really need this?" isn't exactly a question about "sparking joy", but I hope it will be just as effective.

__________

[categories]

personal, general, travel

|

link

|

Thursday, 30 November 2023

10:34 PM

Recently I was at a grocery store in our neighborhood that still does a lot of business in cash. As I was waiting, I watched the cashier ring up the customer in front of me. The cashier deftly took the customer’s bill—a $50, I think—and counted out change. When it was my turn, I said “It looks like you’ve been doing this for a while”. “Oh, yes”, she said. “35 years”.

During my college years (1970s), I had a kind of gap year during which I worked for Sears, the once-huge department store. I was hired as a cashier, and the company put us through an extensive training program for the position.

For example, that’s where I learned something that I saw the grocery-store cashier do: when you accept a big bill from a customer, you don’t just stuff it into the tray. You lay it across the tray while you make change. That way, if you make change for a fifty but the customer says, “I gave you a hundred”, you can point at the bill and show that that’s what they’d given you.

Before my timeMy cashiering days were at the beginning of the era of computerized cash registers (no big old NCR ka-ching machine for us). Although our register could calculate change, they still taught us how to count out change manually. (One method is to count up from the purchase price to the amount the customer gave you, as you can see in a video.)

We also learned to handle checks, which included phoning to get an approval code for checks over a certain amount. We learned to test American Express travelers checks to see if they were authentic. We learned to handle credit cards, which we processed using a manual imprinting machine that produced a carbon copy of the transaction.

We also learned to be on guard for various scams, such as the quick-change scams that try to confuse the cashier, as you can see in action in the movie Paper Moon.

There was of course lots more—cashing out the register, doing the weekly “hit report” of mis-entered product codes or prices (this was also before UPC scanners), and many other skills associated with being at the point of sale and handling money.

During my son’s college years (late 2000-oughts), he also worked as a cashier, in his case for Target and for Safeway. I quizzed him about his training. He remembered that the loss-prevention people at Target warned them about the quick-change scam, and it even happened to him once while he worked at Safeway.

But he doesn’t remember much training about how to handle change; at a lot of places, coin change is automatically dispensed by machine into a little cup. He does remember learning how to handle checks. But he doesn’t remember much training about how to handle change; at a lot of places, coin change is automatically dispensed by machine into a little cup. He does remember learning how to handle checks.

Most of their training, he remembers, was about how to use the POS terminal[1]—how to log in, how to enter or back out transactions, etc. A POS terminal is, after all, a computer—they were being trained in how to manipulate the computer, and less so than in my day about how to handle cash money.

Shortly after I had my grocery-store experience with the experienced cashier, I was in line at a local coffee shop. The customer ahead of me paid in cash. When I got to the counter, I asked the amenable counter person, “This is going to be a sort of weird question, but how much training did they give you in how to handle cash?” “Little to none”, was her report.

And Friend Alan recounted this experience recently on Facebook about a cashier trying to figure out how to even take cash:

It might seem like old-school cashiering skills are becoming anachronistic. It’s not unusual in my experience that small shops and pop-up vendors only take cards, using something like Square. Frankly, I was surprised that the coffee shop with the informative counter person even took cash. It might seem like old-school cashiering skills are becoming anachronistic. It’s not unusual in my experience that small shops and pop-up vendors only take cards, using something like Square. Frankly, I was surprised that the coffee shop with the informative counter person even took cash.

Moreover, we customers are more and more becoming our own cashiers. Many stores nudge customers toward self-checkout kiosks, in part by reducing the number of cashiers so that it’s faster to use the self-checkout.[2] The logical conclusion to this effort is the cashierless store (aka “Just walk out store”), where computers just sense your purchases and charge you.

Still, it’s not like cash is going to go away. Even in the age of debit cards and Venmo, people will still want to use cash for various private transactions.[3] Moreover, not everyone has a bank account, or wants one. Although individual merchants might decide to go card-only, many will still find it to their benefit to take cash.

That probably will continue to include the grocery store where I met the experienced cashier. For the sake of that store, I hope that she is able to pass her experience and training on to other cashiers who work there.

__________

[categories]

personal, general, technology

|

link

|

Monday, 28 February 2022

11:32 AM

No wonder Amazon is eating their lunch

Our local pool finally reopened recently, so I'm making one of my periodic attempts to get back into swimming. I have long hair, and the last time I went, I thought, you know, I should get a swim cap.

I researched and learned that there is such a thing as a cap for long hair (i.e. fits over a bun, I guess). So yesterday, Sunday, I betook myself to the local shopping center to go to the sports store. I'm always hesitant about the place because they seem to be, as we say at our house, run by children: the average age of the sparse staff seems to be in the low 20s or thereabouts. But it was local and open.

I found the section for swim caps. They had no long-hair swim caps at all, but they did have a normal silicone cap that I thought might do. In fact, they had two identical packages of them. One was priced at $12.99. The other was priced at $9.99. I found the section for swim caps. They had no long-hair swim caps at all, but they did have a normal silicone cap that I thought might do. In fact, they had two identical packages of them. One was priced at $12.99. The other was priced at $9.99.

I found someone who was working there and asked, "Do these seem different to you somehow?" No. So it was odd that they were priced differently, right? "Let me look that up," the employee said, and went to the register to scan the two packages. After the scan, the employee said that yeah, the price was $12.99. Did I want to buy it?

Dear reader, I now ask you to contemplate whether this could have been an opportunity for a customer-service win.

But the opportunity was not seized. Even though I was holding a package in my hand that was clearly labeled $9.99, they were going to charge me $12.99. And it wasn't even exactly what I was looking for.

I went home and ordered what I needed from Amazon. It was less than $9.99 and it was on my doorstep by 9:30 Monday morning.

Now, I can imagine that some employee had been tasked at some point with updating price tags and had just missed this item. And I can imagine that the employee I talked to was not authorized—in fact, perhaps no employee at the store is—to override the price that the computer lists for an item.

I could have sucked it up and paid the extra three dollars for an item that wasn't quite what I wanted. And I could have felt virtuous doing so knowing that I was "supporting local business," although it turns out that this company has over 400 stores spread around the western states.

This is the dilemma of retail businesses. They can't compete directly with online sources on price or selection. But they have to offer something that makes up for this besides simply being local. Good customer service is a possibility. Knowledgeable staff. The instant gratification of walking out of the store with what you went there for.

There's a local hardware store with 7 outlets in the Seattle area that does this right. They compete with Home Depot and Lowe's (often close by), but they are generously staffed with people who know what they're talking about. Most of the stores are big, and although they don't stock as much as a Home Depot, they stock some of the weirder things you might need, and as noted, they have people who can help you find that thing and can then tell you how to use/install/fix/wire/paint it. I will always go to this store first, and I am willing to pay the "local" price, which is often 10–20% higher than what the box stores charge.

So "shop local" can be a good experience. But, as my sports-store experience suggested to me, local is not by itself enough to compete.

What are your thoughts?

[categories]

general

|

link

|

Sunday, 6 June 2021

01:23 PM

Over the last year and some, we didn't dine out, obviously, since we couldn't. Now that we're easing back into more normal life, I've realized that a year away from the lure of going out to eat has changed my thinking about it a bit.

Of course, many restaurants survived by offering take-out food. We got take-out a few times. But I realized that I didn't like this very much. For one thing, the third-party delivery services have been accused of some shady practices. But even if you order directly from the restaurant, it's a suboptimal experience. My summation of the experience of take-out food is this: cook something; leave it sitting for 20 minutes; serve and (probably don't) enjoy. Now I get take-out only if I intend to eat it more or less immediately. Of course, many restaurants survived by offering take-out food. We got take-out a few times. But I realized that I didn't like this very much. For one thing, the third-party delivery services have been accused of some shady practices. But even if you order directly from the restaurant, it's a suboptimal experience. My summation of the experience of take-out food is this: cook something; leave it sitting for 20 minutes; serve and (probably don't) enjoy. Now I get take-out only if I intend to eat it more or less immediately.

One of the first things that changed was that we cooked more at home. I'm a, dunno, utilitarian cook: I can make a certain number of things, but I don't aspire to fancy cooking. What the enforced time away from restaurants did, though, was to encourage me to work on cooking things I like. For example, I like going out for diner-type breakfast. Over the last year I actively worked on re-creating that food at home. This was a success for me: I've made waffles, hash browns, eggs over easy, French toast, and hash that to me was entirely satisfactory. (I emphasize that I can now cook these things the way that I like them, not that I should work in a diner.) There are also lunch and dinner foods that I feel that I've perfected for my individual taste. (Same caveat.)

Homemade hashbrowns and eggs Homemade hashbrowns and eggsThis success has made me ponder the purpose of going out to eat. Certainly I (you too?) have paid for pretty indifferent restaurant meals. At this point, I ask myself why I should go out for a breakfast that I can probably do better (same caveat) at home. Should I wait in line on a Sunday morning to eat a mediocre breakfast? Do I really want to go out for another meal of American Mexican food? I'm beginning to wonder.

Then there is the cost. Any sit-down meal is going to cost $18–20 per person and of course can cost many times that. If I go out for dinner with my wife, we can easily be looking at, what, $50 at even a two-$$-sign restaurant, especially if we get drinks. If one or more of the kids come along, multiply that number. It's not that these prices are unreasonable; it's that it adds up. How much per week should I budget to get meals that have a likelihood of being pretty forgettable?

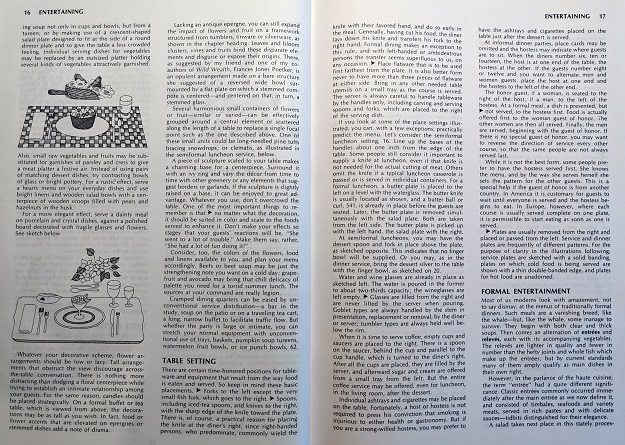

But dining out is not just about meals that you might or might not be able to make at home. Going out is about third places—not home, not work, but a third place. For example, unlike my parents' generation, we don't "entertain" at home in the way that seemed to be a premise in many 1950s-era cookbooks. If we want to socialize with people, our custom (and I suspect that of many folks) is to meet up for coffee or lunch or a beer. Obviously, socializing over a table—socializing at all—was severely constrained over the last year and some.

Pages from "The Joy of Cooking" (1975) about entertaining Pages from "The Joy of Cooking" (1975) about entertainingMy wife and I also enjoyed taking our laptops to a coffee shop or pub and working or writing. (I wrote many blog posts at an ale house that was within walking distance of our last domicile.)

Did these protocols change over the pandemic time? I have started meeting people again to catch up, and it's the same as before—find a place convenient to both parties, and then have breakfast or a beer or whatever. But I am much more aware now that I'm paying to socialize, so to speak, and I'm maybe a little more resentful when I shell out a hunk of money for something that wasn't very good, the company itself of course excepted. (It's great to see people in person again.)

Based on my limited experience again of working or writing away from home, I know that I still enjoy that. Coffee shops are opening up again to allow people to sit and work; my wife and I spent a couple of pleasant hours at a coffee shop a few Sundays ago plugging away on our respective writing projects.

Back to writing at coffee shops Back to writing at coffee shopsIt would be easy to get back into a habit of going out 4 or 5 times a week to do this. But it's possible that pandemic-time habits have made me rethink all this. Although it will be easy again to think that I'm too tired to make dinner at home and go out, I've gotten out of the habit. I think about whether I'll enjoy it and how much it costs. The same is true for grabbing the laptop and settling at a table somewhere to work. Fortunately, our libraries are opening up again to allow people to sit and work: a third place that doesn't cost anything to use (though the hours are not always convenient).

I don't think we'll change our socializing habits, though; I anticipate that we'll still meet people out in the third place. But the pandemic reset expectations about socializing, I think. We went months without seeing anyone in person, and I'm still okay with limiting face-to-face socializing to just occasionally, maybe a couple of times a month at most. In this regard I think I differ from my wife, who is not as content as I am to have long periods between visits.

I've read a number of articles about how there's pent-up demand for things to get back to how it was in pre-pandemic times. I suspect, though, that for some of us, the forced changes over the last year have done a reset on our expectations and, possibly, on our habits.

[categories]

personal, general

|

link

|

Monday, 23 December 2019

08:07 AM

Christmas carols are songs that you learn as a youngster, at an age when you don't spend too much time thinking about the lyrics. Everything else is sort of mysterious when you're a kid, and the oddball words to seasonal songs are just one more thing you don't quite get.[1]

By the time you're an adult, the songs are ingrained, and you probably don’t spend too much time thinking about the lyrics. Or at least not the lyrics that you mostly know, namely those in the first verses of all your favorites. By the time you're an adult, the songs are ingrained, and you probably don’t spend too much time thinking about the lyrics. Or at least not the lyrics that you mostly know, namely those in the first verses of all your favorites.

But I went to a Christmas carol sing-along the other evening, during which we sang verses two and beyond. I guess I was surprised at a few of the weird turns that otherwise familiar songs took when we got past that one verse that you know. Herewith a few examples.

"Hark! The Herald Angels Sing," verse 2:

Christ, by highest heav'n adored:

Christ, the everlasting Lord;

Late in time behold him come,

Offspring of the favored one.

Veil'd in flesh, the Godhead see;

Hail, th'incarnate Deity

Seriously, I had to stop singing and marvel at "Offspring of the favored one."

"Away in a Manger," verse 4:

I love Thee, Lord Jesus, look down from the sky

And stay by my cradle 'til morning is nigh.

I thought that took quite a turn toward the personal. Also, … cradle?

"Jingle Bells," verse 3:

Now the ground is white

Go it while you're young

Take the girls tonight

And sing this sleighing song

Just get a bob tailed bay

two-forty as his speed

Hitch him to an open sleigh

And crack! you'll take the lead

As someone sitting behind me said, "Uh-huh, now we know what that's about."

Guess the song:

For lo! the days are hastening on,

By prophet bards foretold,

When, with the ever-circling years,

Shall come the Age of Gold

Apocalyptic much?

This is not even to mention the vocal machinations it took to cram or stretch some awkward lyrics into the familiar tunes, all in real time. (Did not always succeed.)

If nothing else, I learned that people's ability to versify was not significantly better in, say, the 19th century than it is now. This gave me … comfort and joy. :)

[categories]

general

|

link

|

Sunday, 14 October 2018

07:00 PM

I commute to work on crowded mass transit, and when I get there, I work in an open office. So I consider good headphones an essential part of my gear. My employer apparently agrees; they subsidize headphones for us. I’ve appreciated the pair I got: over-ear, noise-reducing, Bluetooth headphones. I use them for hours a day every workday.

But the daily use has taken a toll. A few months ago I noticed that the headphones seemed loose on my head. Close examination revealed that the plastic arch between the earpieces had cracked. Thus began an ever more involved effort to save these lovely headphones. But the daily use has taken a toll. A few months ago I noticed that the headphones seemed loose on my head. Close examination revealed that the plastic arch between the earpieces had cracked. Thus began an ever more involved effort to save these lovely headphones.

Bridging the crack

My first thought was to patch over the crack. I found a washer that was about the size of a quarter, and used epoxy to glue the washer across the crack, then taped it over to salvage some semblance of aesthetics. (Ha.) was a little dubious about this, but it actually worked ok.

However, a few weeks later the headphones were loose again. I thought my patch had failed, but no—a second crack had appeared at a different point. It seemed clear that there are stress points in the headphones:

I tried a second patch like the first one, but a third crack developed.

Repair or replace?

After this discouraging development, I spent some hours online looking for a replacement for my headphones. I looked and looked, but two things ultimately stopped me from buying a new pair. One was that omg, headphones that have all the features I want (NR, Bluetooth, over-ear, decent audio) are expensive. And to add to this disheartening discovery, many reviews suggested that many other brands of headphones were probably just as prone to breakage as the ones I already had. So I returned to the idea of trying to engineer a fix for the ones I already had.

Brothers of bands

After the severally patched cracks had failed, I kept thinking that I needed to in effect make a new arch for the headphones. I needed some sort of spring-like band of material that I could attach to the headphones. (Some people might already have thought about an obvious solution, which I arrived at later; bear with me a few moments.) I kept thinking about some sort of plastic, but couldn’t arrive at a material that was both flexible enough and had enough spring. What I eventually did was to cut apart the plastic jar from a well-known brand of popcorn and laminating four layers. This seemed to provide the right amount of spring:

I then taped this ad-hoc spring to the headphones with lots of tape, even further reducing their visual appeal:

(I swear that I catch people on the train looking at my jury-rigged headphones and wondering “What the heck is that?”)

Is there a spring for the head?

This worked pretty well for a couple of months. But inevitably, my plastic spring started losing some of its sproing, so I was back to thinking about a better way to make this fix. It finally occurred to me that there is a device that is pretty much designed for this exact purpose: headbands for hair. I betook myself to the beauty section of the local drugstore and pondered my many choices. I ended up with a set of thin metal bands:

I disassembled and reassembled the headphones, this time adding one of the metal headbands to the arch. (I don’t want them to be too springy, because I wear the headphones for long periods and don’t want to squash my ears.)

And that’s where I am today. I’m hoping that this repair, or if necessary, another one like it, will hold until the electronics fail, or I step on them accidentally, or I have some other reason to buy a new pair. And next time I’ll have a head start on ways to fix the headphones when they start cracking.

[categories]

personal, general, technology

|

link

|

Sunday, 8 July 2018

11:33 PM

The other day I was taking an introductory training class for some technology at work. There was a slide that outlined the technology, and one of the bullet points had an asterisk next to it. At the bottom of the page was this footnote:

Most strong statements like this are only mostly true. Don’t worry about it.

I had to stop for a while to ponder the pedagogical implications of this footnote.

There's an inherent problem in trying to describe something complicated to a newbie: how do you start? If someone knows absolutely nothing about, say, playing bridge, or verbs in Spanish, or physics, or grammar, you have to give them a large-picture, broad-stroke overview of this thing they're about to dive into.

This is hard. One reason is that people who are familiar with some domain frequently have difficulty coming up with sufficiently high-level overviews that make sense to a beginner. I've had a couple of people attempt to explain the game of bridge to me, but they could not come up with a simple, comprehensible explanation of the bidding process.[1] This is hard. One reason is that people who are familiar with some domain frequently have difficulty coming up with sufficiently high-level overviews that make sense to a beginner. I've had a couple of people attempt to explain the game of bridge to me, but they could not come up with a simple, comprehensible explanation of the bidding process.[1]

A closely related reason is that experts often cannot let go of details. For example, in your first week of Spanish class, the teacher tells you that the verb hablar means "to speak," and that to say "I speak" you cut off -ar and add -o: hablo. And that this is the pattern for any verb that ends in -ar. So to say "I take," you use the verb tomar and turn it into tomo.

Easy! Powerful! Also, of course, only mostly true: there are irregular verbs and reflexive verbs and other fun. But throwing those additional details at you in the first week of Spanish 101 is counterproductive. There will be time to sort out the exceptions later, once you understand some basics.

I took physics in high school, and when you start, you're learning a lot about f=ma. I have memories of homework problems involving blocks being pulled or pushed, and the problems always said something like "… ignoring the effects of air resistance." A beginning physics student has enough to think about when calculating the effect of gravitational acceleration without trying to factor in air resistance and all the other real-life variables that come into play. In fact, there's a well-known joke in the physics community about a "spherical cow" that represents the ultimate in simplifying a model.

One more example. In the linguistics community, it's widely discussed that even if kids are taught grammar, it's not taught very well. People who are experts in grammar will sometimes complain (example) that the explanations we give students are hopelessly simplistic. "A noun is the name for a person, place, or thing," goes a typical definition. This doesn't adequately cover gerunds ("Smoking is bad for you") or concepts ("Orange is the new black") or many other ways in which we noun things.

But this gets back to the point. If you're faced with a classroom of 8-year-olds, how do you tell them what a noun is? Using terms like "lexical category" and "defined by its role in the sentence" is not going to work. You have to start somewhere.[2][3] But this gets back to the point. If you're faced with a classroom of 8-year-olds, how do you tell them what a noun is? Using terms like "lexical category" and "defined by its role in the sentence" is not going to work. You have to start somewhere.[2][3]

And that means ignoring messy details. As one of the commenters on the linked grammar post describes it, "It's quite normal for us to use 'lies to children' in education." Or, to get back to where we started, you sometimes have to make strong statements that are only mostly true.

[categories]

general, teaching, writing

|

link

|

Monday, 20 November 2017

09:30 PM

I find it harder and harder these days to ride as a passenger when other people drive. Some of that is just part of

getting old. But it's not just that; as I've noted before, learning to ride a motorcycle has

helped make me a better

driver.

One tactic I've worked on is how much space I leave between me and the driver in front of me. To my mind, most people

follow too close. You really don't want to do that. Here's why.

Note: If you want the tl;dr, skip to So what do I do?

Speed and distance

Let's start by examining what sort of distance you're covering when you drive, because it might be more than you

think. At 10 mph, in 1 second you cover about 15 feet. At 70 mph, in that same 1 second you cover 103 feet. Here's a

graphic that illustrates this ratio.

An accepted measure of a car length is 10 feet. This means that if you're going 60 mph, in 1 second you will travel 9

car lengths. Even small differences in speed result in significant differences in how far you travel—the difference

between driving at 60 and at 70 is that in 1 second at 70 you will travel an additional 15 feet (88 vs 103).

More than one car length.

Braking distance

Let's imagine that for some reason you have to slam on the brakes. Alas, physics tells us that you cannot stop on the

proverbial dime. The faster you're going, the longer it takes to get to zero mph.

There's no standard chart for stopping distance for cars. Cars weigh different amounts and they have different

brakes; for example, newer cars have anti-lock brakes a.k.a. ABS. (Jeremy Clarkson of the TV show "Top

Gear" also makes the case [video] that

cars that are engineered to go fast are also engineered to stop quickly.) External factors also come into play, such

as the road surface (wet? gravelly?) and the tires on the car. Also whether you're going uphill or downhill.

Anyway, it's complex. The best that people can offer is a minimum braking distance based on a formula

that takes into account the initial speed, the car's mass (weight), and the friction coefficient of brakes and road.

I'll spare you that here, but I'll suggest some ballpark numbers, as shown in the chart. (You'll see a variety of

numbers for this measure if you look around; these are actually on the low end.)

Notice that braking distance at 60 is 180 feet—18 car lengths. That's about 1 city block. Going 70, which of

course is only 10 mph faster, the braking distance goes up to almost 250 feet, or an additional 7 car lengths.[1]

Reaction ("thinking") distance

Braking distance is measured from the time the brakes are engaged. But everyone will remind you that there's a delay

between the time you see that you have to brake and when you finally get your foot onto the pedal. Remember from the

earlier bit that if you delay one second before you hit the brakes, your car might already have traveled many car

lengths before you even start slowing down.

The combination of reaction distance and braking distance is referred to as the total stopping distance.

Since I'm all about the pretty charts today, here's one from the UK that shows the total stopping distance as

"thinking distance" plus braking distance (click to embiggen):

It's the total stopping distance that matters when you're driving behind someone: how far will you keep going before

you can stop if something happens ahead of you? Or stated another way, is there enough room between you and the car

ahead so that if they slammed on their brakes, you could avoid slamming into them?

As with braking distance, there's no standard measurement for reaction distance. Some people have faster reflexes

than others. But even lightning-quick reflexes result in some delay between stimulus and reaction.

And much more importantly, some people pay closer attention to traffic than others. People text while they drive,

they yack with their passengers, they watch their GPS, they fool with their radio, they search the passenger

footwell for their dropped phone, they watch TV while driving. There have been

accidents where the driver behind never hit the

brakes at all. In our little car bubble, we sometimes forget that we're piloting 1 ton or more of iron at 88

feet per second, something that's not scary only because we're used to doing it.

And it's your fault

The law generally puts the responsibility on you to leave enough distance. If you rear-end someone, it will almost be

always considered your fault. There are a few circumstances when you can make a case that the

driver in front contributed to the accident, but the default assumption will be that you were not driving in a safe

manner. Not to mention, I suppose, that if you have an accident, you will have had an accident, with all the hassle

that that entails.

Think of the traffic

Even if you have superhuman reflexes and a physics-defying vehicle that can stop on a dime, leaving a gap between you

and the car in front can have benefits for overall traffic flow. By leaving a gap, you can actually minimize the

accelerate-then-brake cycle that characterizes most heavy traffic.

Imagine that you’re behind someone and they tap their brakes to slow down by 5 mph. If you’re close, then you, too,

have to tap your brakes to slow down. Even this small slowdown, and even if both of you immediately speed up again,

creates a kind of wave that moves backward through traffic. In fact, this is sometimes the source of “phantom”

slowdowns on the freeway, where everyone slows down for no apparent reason.

However, if you’re far enough behind someone, when they tap their brakes, you might not need to tap yours at all, or

you can slow down enough just by easing off the accelerator. And if you don’t have to, the person behind you doesn’t

either, and so on backwards through traffic. Result: possible traffic jam averted.

The engineer William Beatty refers to this as

"eating" traffic waves. He explains: By driving at the average speed of traffic, my car had been "eating"

the traffic waves. Everyone ahead of me was caught in the stop/go cycle, while everyone behind me was forced to

go at a nice smooth 35MPH or so. My single tiny car had erased miles and miles of stop-and-go traffic. Just one

single "lubricant atom" had a profound effect on the turbulent particle flow within miles of "tube."

Obviously, there are limitations to this; if traffic is completely stopped, it’s just completely

stopped. But if you can help reduce traffic jams by leaving a little extra space between you and the next person,

isn’t that a worthy goal?

So what do I do?

When I got my license many decades ago, the rule was to leave 1 car length ahead of you for every 10 mph. If you're

going 60 mph, 6 car lengths. As you can see from the various distances listed above, that's probably not enough. And

that's even assuming that you can estimate car lengths correctly, which I think a lot of (most?) people cannot.

(Little-known fact: the dashed white lines between lanes on the freeway are 10 feet long.)

When I got my motorcycle license, I learned a far more useful guideline: the three-second rule (PDF). The idea is that

when the car ahead of you passes some landmark (a streetlight, a sign, anything static), you

count "one-thousand-one, one-thousand-two, one-thousand-three." If you reach the landmark before you finish

counting, you're following too close. The rule is useful because it's independent of speed—the faster

you're going, the longer the distance is that you go in 3 seconds, so it (kind of) works out. Naturally, this is

just a rule of thumb, which has to take into account all the factors that go into how quickly you can stop. But

it has the advantage that if you routinely practice counting off your 3 seconds as you drive on the highway, it

means you're paying attention, and that's a very big factor in how safely you're driving.

Event horizon

As if it isn't hard enough just to pay attention to the car in front of, you really should be aware of what's going

on in front of them. The same motorcycle manual that recommends the three-second rule suggests that you try

to see what's happening 12 seconds ahead of you. This is sound advice, because the driver

in front of you might not be paying close attention. If you see that the driver ahead will have to slow down even

before they're aware of it, you can adjust your own driving accordingly. (This is captured in the concept of assured clear distance

ahead, which you can read about in a particularly poorly written Wikipedia article.)

By the way, all of this applies also to cars behind you, and to your side. Driving safely is hard work.

If you can't see ahead of the car in front of you, it's best to leave even more room than you normally

would. I actually have this problem a lot. The motorcycle isn’t very tall, of course. And my normal car is a MINI,

which sits pretty low to the ground. In both cases, if I'm behind an SUV or pickup or anything larger than that, I

have no clue what's going on up front.

Parting notes

People have pointed out that if you leave gaps ahead of you, other drivers will swoop in. That's true. If you have

completely mastered the zen of good following practice, you just let them, and you slow down to again open up a

suitable gap ahead of you. I will acknowledge that this is a state of driving enlightenment that most of us can only

aspire to. Still, it has helped me to think holistically about safety and about traffic, and if I’m in just the

right frame of mind (like, not late to an appointment), I can do a decent impression of someone who actually has

mastered all this. And of course, if I'm on the motorcycle, I am ever mindful that even a small miscalculation in

how closely I follow can have grave consequences.

For the most part, driving is uneventful. Even if we speed, even if we speed and follow too closely, mostly things

don't happen. But it's this very uneventfulness that can make us complacent and lead us to stop paying close enough

attention to an activity that can wreak mayhem in the "unlikely event of" a crash.[2]

[categories]

technology, general, motorcycles

|

link

|

Monday, 10 November 2014

10:26 PM

Sarah and I have been engaged in a gradual process of downsizing, and one of the ways we’ve been doing that is by shrinking our extensive collection of books. Not long ago we did another round of culling and pulled five boxes of books off the shelves. Then, in keeping with what we’ve done many times before, we lugged our boxes around to bookstores in order to sell them.

Prior experience suggested that we’d have the best luck with specific bookstores. Several times I’ve sold books to Henderson’s and Michael’s in Bellingham; the former in particular has always paid top dollar for books, which is reflected in their excellent on-shelf inventory. We have reason anyway to occasionally visit Bellingham, so not long ago we hauled our boxes northward.

But it proved disappointing. We used their handcart to wheel our five boxes in; the stony-faced buyer picked out about 25 books, and we wheeled five boxes back to the car. Michael’s, which is across the street from Henderson’s, was not buying at all, only offering store credit.

With diminished enthusiasm, we headed back south. Our next stop was Third Place Books in Lake Forest Park. Like Henderson’s, they carefully picked out a small stack of books and gave us back the rest. Although I was tempted to visit Magus Books in the U District—in my experience, they’ve always been interested in more academically oriented books—the day had already gotten long for little gain. Therefore, our last stop was Weasel Half-Price Books, which gave us a handful of change for the remaining four boxes. Presumably we could have demanded back the books they were not interested in, but by then we we'd lost pretty much all of our energy for dealing with the boxes, even to donate them to the library.

All in all it was a heartbreaking experience. The web has been a good tool for those who like books. Sites like Abebooks have created a global market for used books, so that a place like Henderson’s can offer its inventory not just to those in the environs of Bellingham, WA, but to anyone with an internet connection. But the internet has also brought a lot more precision to this market; a bookseller has a much better idea today of what a book is worth—or not worth—on the open market. One effect certainly has been that the buyers at all these bookstores are much choosier than they might have been 15 years ago, when (I suspect) buying decisions were still reliant on a dash of instinct.

More than that, and a fact that’s hard for me to accept, is that used books are a commodity of diminishing value. We collected those books over decades, and each acquisition had personal meaning to us. I could easily have spent an hour pulling books out of the boxes and explaining to the buyers at Henderson’s or Third Place or Half-Price why I bought the book, and when, and why I’d kept it all these years, and why it was a book sure to appeal to some other reader. But they don’t care about your stories, a fact that’s all too obvious when you’re standing at their counter, meekly awaiting a payment that represents a tiny fraction of your investment—financial and otherwise—in the books you’ve handed over.

No one really wants my old VCR tapes or CDs or even DVDs much anymore, either, although I don’t have as much emotional investment in those as I do in books. And I can’t really fault booksellers for their choosiness, since their continued success is dependent on hard-headed decisions about their inventory.

We still have five bookshelves filled with books at home, and we'll continue to downsize. I think I might be done with trying to sell the books, though. I'm not sure I want to experience the sadness of seeing how little all these lovely books are worth to anyone else but us.

[categories]

general, personal

|

link

|